Cure for AIDS

Wilmington Lawyer Tells of His 10-Year Struggle to Reveal a Possible Cure for AIDS

By MARK NARDONE

Big Shout Magazine, June 1993

If ignorance leads people down the road to AIDS, then ignorance is preventing researchers from finding a cure.

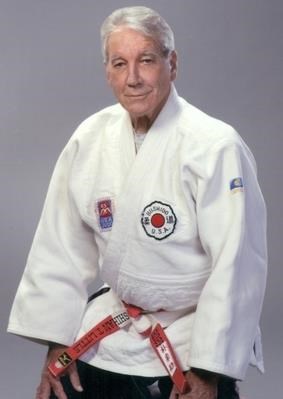

So says Tom Little, a public defender for Family Court in Delaware. The AIDS issue has tormented him for almost 10 years, and for good reason.

Little claims to know the cure for acquired immune deficiency syndrome.

According to him, human placenta, combined with saliva — the beginning of the immune system — will destroy AIDS-causing human immuno-deficiency virus.

But despite the medical community’s reborn obsession with fetal tissue research, he has been unable to persuade anyone to test his idea.

“It’s ignorance, pure ignorance,” Little says, and it’s driving him mad. “It’s a simple word bias. Placenta is fetal tissue, but no one wants to recognize that.”

Little knows he is treading on the delicate sensibilities of most people, including many medical researchers. But anything with even a remote chance of success, he says, should be tested. “There are people with AIDS all over the world who will try anything,” he says.

Little’s obsession with AIDS began with his interest in hypnotherapy. Several years ago, he discovered that he could help an elderly neighbor, crippled by polio since childhood, regain the use of her legs by power of suggestion.

Little placed the woman in a hypnotic trance for short periods several times per week. In such a state, she could return subconsciously to an age when she could run, walk, and jump. Over time, her brain began to create hormones that strengthened her legs.

With his success, Little began to help others with less serious afflictions. Then, while meditating one day, a possible cure for AIDS struck like a bolt from the blue.

Experienced in handling the media from his days as a state representative, Little called a press conference to share his idea. A handful of reporters showed, but Little saw nothing about it in the next day’s papers.

“They thought I had completely gone over the edge,” he says. “They thought I was really nuts.”

He was discouraged, but he continued clipping articles from newspapers and magazines that pointed toward the correctness of his case. Then he found a missing link.

In December of 1991, The Lancet, Britain’s most prestigious medical journal, published a study of 100 sets of twins born to women infected with AIDS-causing human immuno-deficiency virus.

One third of the twins were born with HIV. Each of the infected twins was born first.

The authors of the article speculated that the first twins cleared the birth canal of HIV during the passage, leaving it safe for the second born. The babies were not, they concluded, infected in the uterus.

To Little, the survey is strong indication that placenta has remarkable protective properties. “The placenta is just as smart as the AIDS virus,” he says. “And that AIDS virus hasn’t been around for just a few years.”

Whether placenta acts as a filter for HIV or whether it contains a hormone that destroys the virus, he doesn’t know. “I’m a lawyer, not a doctor,” he says. “But the essence of a cure for AIDS lies in the human placenta. Anyone who can make a statement like that and back it up ought to be listened to.”

But even researchers at the National Institute for Allergies and Infectious Diseases (NIAID), which supported The Lancet’s twins survey admit they don’t understand placenta’s role in HIV transmission.

“Someone, however, must find out,” Little says. He showed The Lancet article to everyone he knew who had an interest in the disease, including fellow members of a now-disbanded statewide commission on AIDS. “Their reaction was, ‘Jesus, Tom, you’ve been telling us this for years!”

Little called local newspaper editors. Again, they failed to print his story, even though The Lancet article was the subject of an Associated Press story published by The News Journal.

Then Little contacted old friends from his days in the state House of Representatives. The office of Sen. Joseph R. Biden, Jr. sent a copy of The Lancet article to Dr. William Loper, director of the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) in Atlanta, asking whether its findings merited more research. “We did it for Tom like we’d do something for any constituent,” says Biden’s press secretary Mike McCabe.

Then Little persuaded Sen. Herman M. Holloway Sr., to introduce a Senate resolution. The resolution acknowledged that Little’s belief about a cure for AIDS could be wrong, but it also could be right.

“Toms’ got some peculiar beliefs, but as far as I’m concerned, he’s a decent, honorable man. I was glad to help him,” says Holloway, former chairman of the Senate Committee on Health and Human Services.

The resolution passed last June. It requested that Biden report the CDC’s determination on The Lancet article to the state legislature. But the CDC, more concerned about AIDS education than research, sent the article to the NIAID, where it was ignored. After all, NIAID admitted it doesn’t understand the link between placenta and HIV transmission.

Besides, according to NIAID spokeswoman Mary Jane Walker, there is no evidence to back Little’s proposition. “Someone would have to present a very credible study to indicate such a treatment might work before we would even begin testing,” she says.

But NIAID, Little points out, has evidence it generated itself. All he has done is introduce saliva into the equation — and, he says, shifted the burden of proving or disproving his idea to the medical community.

“It’s a simple test,” he says. “Take a drop of blood infected with HIV and put it on a slide. Stick it under a microscope and look at it. Then add a drop of saliva. I guarantee you’ll see a change in that virus. But no one wants to touch it.”

Little blames NIAID’s unwillingness to test his idea on the former Bush Administration, which banned research on fetal tissue and prohibited federally-funded family planning clinics from mentioning abortion to clients.

“George Bush and Ronald Reagan were totally paranoid about abortion and rejected every idea inconsistent with their philosophy,” Little says. “They win the all-time prize for stupidity. God doesn’t make anything that doesn’t have a purpose.”

He points to advances in fetal tissue research, which has led to successful treatment of Parkinson’s Disease with cells extracted from human umbilical cords.

Now, 12 years of Republican rule, social conservatism, and moral self-righteousness are out. Bill Clinton and his promise of change are in.

“The whole atmosphere has changed,” Little says. “There’s more receptiveness to new ideas.” And he has gained renewed hope that someone will listen to him.

Since the presidential inauguration in January, Bush’s ban on fetal tissue research has been lifted, and Newsweek has published cover stories on the latest fetal tissue research and new advances toward a cure for AIDS.

“Bill Moyers’ Healing Mind” has been aired on public television, evidence of growing media interest in alternative healing, and the National Institutes for Health has established the National Institute for Alternative Medicine (NIAM), a tacit acknowledgement that modern medicine is not the final authority.

Now Little’s crusade has changed. More than ever, he wants someone with medical credibility to test his idea, but he is also battling the ignorance that has prevented researchers from accepting placenta as fetal tissue.

“No one wants to solve problems anymore — they just want to define them,” Little says. “I’m just trying to shift their focus to the other end of the barbell. It’s a compulsion that’s driving me mad. Why are people so closed minded?”

Little views NIAM as his last hope. He is gathering every news article on AIDS he has collected, every piece of correspondence, the Senate resolution and desperate letters that implore researchers to test his idea. He will send the package this week to Dr. Joseph Jacobs, director of NIAM, and wait patiently for a reply while thousands more die of AIDS-related complications.

“I’ve been laughed at by everybody who’s had the chance,” Little says. “I’ve spent 10 years and $100,000, ruined my life and my career trying to get the message out. Nobody, outside Tom Little, is willing to carry this ball. Now let them [NIAM] figure out what to do with it.”

And if he fails to make his case?

“I don’t care. I’ve carried this ball long enough. I’ out of it,” he says. “I know when I’ve been beat.”

Editor’s update: According to an obituary on Congo Funeral Home‘s website — “On December 25, 2016, ‘Tommie’ Little passed over to the other side, and this time he decided to stay.”