J.C. Dobbs: Getting Music to the People

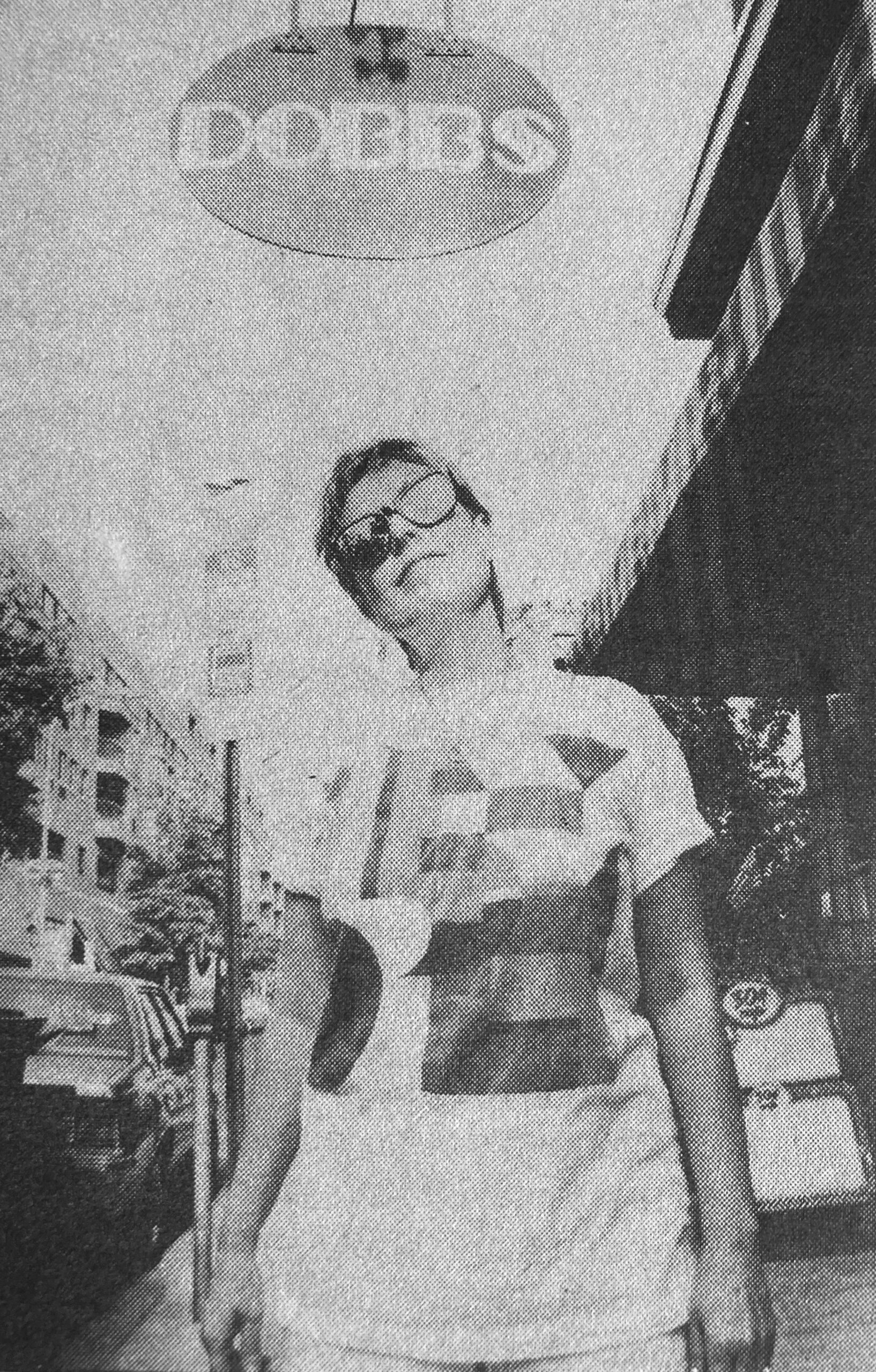

Kathy James standing outside the bar that has made her a nationally-known club owner. (Photo by Gregg Kirk)

Big Shout Magazine, August 1989

By MIKE BRENNER

It’s a gray, lifeless morning on South Street in Philadelphia. Rain slashes down in torrential sheets, driving trash under rows of cars. There is no sign of the street’s usual fanfare. There are no cars cruising slowly, blasting hip-hop. There are no tourists walking into trees while gawking at the nocturnal flora and fauna.

Kathy James makes her way through the rain, clutching what’s left of an old umbrella. The South Street she walks up this rainy morning bears little resemblance to the street she first set foot on 12 years before.

Back then, the walk led James in search of bartending work to a small bar once known as Wexler’s. The bar, which had since changed its name to J.C. Dobbs, had a questionable reputation, due mainly to the black biker crowd that hung out there. It had no kitchen, second floor, or live music at the time.

Now to put it mildly, things have changed. South Street is one of Philadelphia’s main tourist attractions. Many of its small, independently-owned stores have been replaced by the glittery window displays of the nation’s biggest chains. Dobbs however, exists and thrives. It has a kitchen and it has a narrow staircase that stretches up to a second-floor dining area.

It has live music now — seven days a week. And James, the small, fair-haired woman who once worked behind its bar, has become a nationally-known club owner, serving up a wide range of talent from local Philly bands playing their first shows to major-label acts on their first national tour.

“It’s exciting at this level,” says James. “You get to see the bands start out as awkward musicians and see them work toward confidence onstage.” James has had enough opportunity to see these evolving bands. She does 100% of the booking, and it’s a rare night that she cannot be found near the stage, silently eyeing a new band or one that strikes her interest.

“The level of band I book is basically dictated by the capacity of the club, which is fairly small,” she says. “Some bands can fill a bigger place, so they’ll play the Chestnut Cabaret.” Dobbs’ size may exclude some national acts, but by the same token, it’s a great place to see up-and-coming bands like Miracle Legion, Big Dipper, and Evan Johns and the H-Bombs, and stand right up close to the stage.

Dobbs, for many years, was known primarily as a blues bar. The booking policy and huge George Thorogood photos on the wall only reinforced this impression. James concedes she was learning on the job when it came to booking, but now the schedule shows a variety never before seen at Dobbs.

“I went to the New Music Seminar in New York a few years back, and it was real eye opening,” she says. “I found out about national acts, the college music scene.”

James began plugging alternative and hardcore acts into the schedule, along with standard blues and mainstream bands. She notes though that Dobbs is not the only club shifting gears.

“You have to be aware of what’s going on,” she says. “If someone or some kind of music is creating attention in the city, then they deserve a place to play. The Cabarets are also doing more alternative music these days because people want to hear it.”

With the decrease of independent shows, clubs like Dobbs have an even more important role: that of getting alternative music out to the public. While it may seem like a simple job to get a hardcore band to set up and let the spectators run around, throwing themselves off the stage and bashing into each other, it can age a club owner 10 years in a night.

“You want to created the illusion of a wild scene where everyone is excited about the music,” James says, letting a cautious grin escape, “but there has to be some responsibility with the club and the band. People should feel the club is out of control, but a club owner can’t let it get that way.”

On slam dancing at Dobbs, James simply says, “It makes me nervous.”

She still continues to book bands that come equipped with highly-aggressive fans, however.

“I book them on Mondays now, but if they could fill the club, I’d book them on Saturdays,” she says matter-of-factly. “You have to put extra security on front of the stage, but we haven’t had any problems at all.”

Despite an increase in the number of out-of-towners playing Dobbs, the club in James’ words, “was and is local.” And being a local club these days for Kathy James is a good thing to be.

“I think the scene is on an upswing,” she says enthusiastically. “There’s never been a shortage of bands, but now they’re not waiting to get signed to put out albums. Bands know more about what it takes to get a following.” She cites the increased use of band calendars and mailing lists for getting the word out.

“I haven’t seen anything very strong as far as indie labels go, but it’s getting better,” she says, noting that New Jersey’s Skyclad, home of Doctor Bombay, Go To Blazes, and Pink Slip Daddy is a label that’s doing good work.

As for regrets, James sighs and voices a common complaint of anyone in the Philly music scene.

“I just wish this scene was considered national in the way Athens or Minneapolis is,” she says flatly. “Some bands will pass up Philly to spend an extra day in New York doing press.” She hides her annoyance better than most.

Outside, the rain has not stopped. There’s a large body of water stretching from Jim’s Steaks all the way across the street to Copabanana. James mumbles something about having to fix her roof and strides off into the downpour. Rain or not, it’s business as usual at Dobbs. There’s a kitchen to stock, liquor to serve, floors to clean, and most importantly illusions to create.