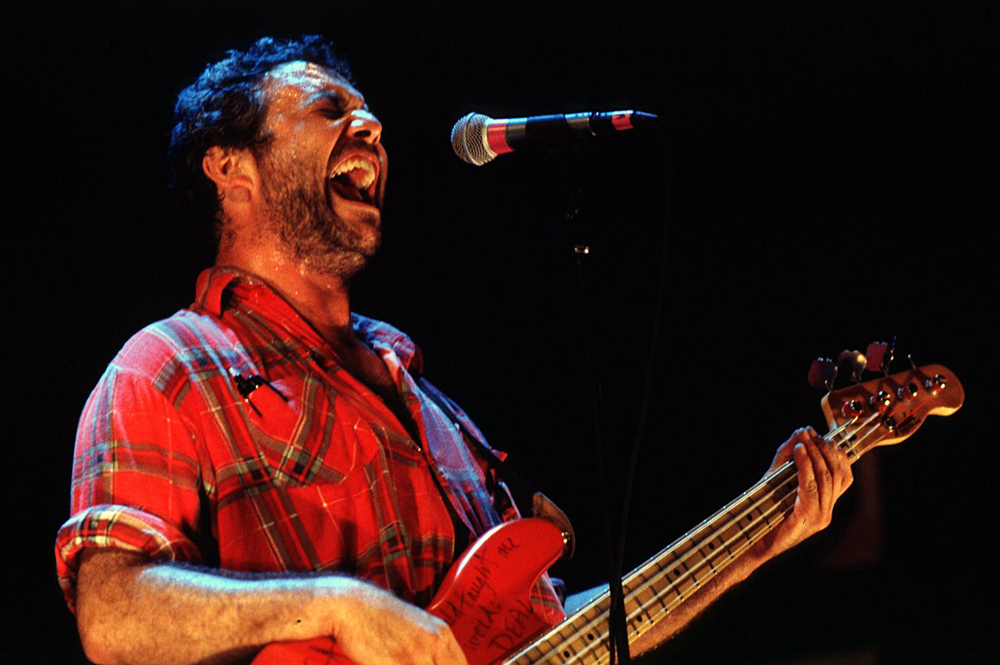

Interview: Mike Watt

By GREGG KIRK

(May 1995, Big Shout Magazine)

Either you know Mike Watt or you don’t. If you do, then you know him as a founding father and bass player from the proto-punk band the Minutemen — a group that splintered when guitarist D. Boon died in a van wreck in 1985. The next year, Watt and drummer George Hurley pulled things together with guitarist Ed (fROMOHIO) Crawford and formed fIREHOSE, which toured relentlessly for seven years and put out five studio albums and one live EP.

After 15 years of touring and playing with only two bands, Watt has made up for lost time on his newly-released solo album ball-hog or tugboat? on Columbia Records. On this release alone he assembles more than 50 musicians, including Nirvana drummer Dave Grohl, Soul Asylum vocalist Dave Pirner, Meat Puppets guitarists Chris and Curt Kirkwood, vocalists Eddie Vedder, Henry Rollins, Evan Dando, Flea from the Chili Peppers, Adam Horowitz from the Beasties… you get the picture.

If you didn’t know Mike Watt, you do now. We talked with him before he hit the Trocadero in Philly on April 26.

Big Shout: Who’s your live line-up?

Mike Watt: It changes. But basically, the Foo Fighters and Hovercraft are playing with me. And the Foo Fighters, when I play, they get up behind me. That’s Dave Grohl‘s band with Pat Smear and two of the kids from Sunny Day Real Estate — Nate and Will.

BS: What happened to fIREHOSE?

MW: Well, I just felt like I was kind of on cruise control there. I mean, for a lot of people it was new, but for me it was seven-and-a-half years, and the last five years it was kinda gettin’ in a rut there. I enjoyed playin’ a lot with those guys and stuff, but it felt like I was just on auto pilot. But I’m gettin’ a band together again. This was just a freak for me to make a record like this. There’s a lot of fuss being made out of it. Basically, what I did was just have these guys come in the studio and have them play the bass line. I had two of the song’s guitar parts, but all of the other ones were just bass lines. And they’d come in there and it was like, “Whoa.” And I said, “Well, whaddya gonna do? Let’s roll the tape.” It was kind of something real spontaneous. It wasn’t like a “We are the World” super champs at all. I mean that’s what the title’s all about — ball-hog or tugboat. It’s, like, where does the bass fit in?

BS: You’re calling this a wrestling record. Did anyone use any illegal holds?

MW: (Laughs) Well, you know… it’s a bass solo record. I mean that sounds like a fusion instructional video. That’s why I called it a wrestling record. I wanted the idea of personalities bouncing on each other. I thought if I made the situation chaotic enough… I was coming from the predictable thing. I wanted to set up a situation where things I couldn’t plan would come up.

BS: Was there anyone you wanted to work with but didn’t get a chance to?

MW: Oh, tons. You know, it wasn’t 50 guys in one room. I did two days in Seattle, two days in New York, and about seven days in L.A. I did 30 songs, really. And it was like 30 little bands. But there was guys like Greg Ginn, Bob Mould, Lou Barlow, Mack from Superchunk — there was a lot of guys I wanted to play with but couldn’t because of touring, not being at the right place at the right time. Luckily, I live in L.A. and there’s a lot of dudes who live there or were touring through there. I got Evan (Dando) in between sound checks; he was playing across the street at Fairfax High. A lot of the stuff was just random, just whoever was there. It was just a freak kind of thing. It is on a big label and stuff, I guess. But I don’t care. I make ’em just like I made my first punk record. Let the freak flag fly.

BS: How much input did you have with everyone’s performances on the CD?

MW: I just handed them the words, and I said, “Here’s the music. Go!” I was the bass player, the rudder man. That was the idea going into it — the tail was going to wag the dog. I gave them a tape of something I made at my house, but see, I wanted to not know what it would be like. That was the whole point of this.

BS: What was the hardest thing about recording it?

MW: Man, when dudes are enthusiastic, you don’t know how easy it is. We turned on the tape, and it was go. The hardest thing was this one engineer I hired — this hippy guy from Malibu. He’s from the old, old school, where there’s big people and little people. He was yelling at the assistants, and anal… 15 hours to do one mix. I threw him over the ropes. He was out. That’s one thing I learned from old punk, man, you take it into your own hands. You don’t let anybody try to tell you the way it is.