EXTREME SPORTS

Kayaker Jeff Kinley braves the surf in Rehoboth Beach

By GREGG KIRK

July 1995

OCEAN KAYAKING

The first thing people asked me when I told them I was going kayaking in the surf was, “What happens if you tip over?” Most folks have the misconception that all kayaks are of the totally-enclosed variety that you see the Eskimos paddling around in somewhere near the North Pole. If you tip over in one of those, you’re kind of screwed unless you manage to pull off a so-called “Eskimo roll” and use your momentum to pop back up. Ocean kayaks are nothing like that. They’re especially made for rough-water conditions — in fact, they’re built so that you can easily fall out of them. Though they may appear a little flimsy at first (especially when you look at the pounding surf and realize that this boat needs to withstand a few jolts from the breakers) they’re made of practically bullet-proof plastic.

My friend Brian lives at the beach and has a couple of ocean kayaks. Several years ago he took me out on the Brandywine River in one, and I have not been in a canoe since. Each year before, I did the obigatory run from the Brandywine River Museum to Thompson’s Bridge in an aluminum canoe, but after making the same run in a kayak, I didn’t see the point of lumbering around in something with the maneuverability of a porcelain bathtub. In a single-man kayak, you can reach places you could never dream of going in a canoe, you can paddle upstream easier, and you can make it through much shallower water without running aground.

The only thing that takes getting used to is becoming adept with the double-ended paddle — and that usually only takes about an hour tops. After we had made a few river and lake runs in the kayaks, Brian took me out to Assateague Island, where we hit the surf.

As you might imagine, ocean kayaking is a lot different than river or lake kayaking. First of all, getting in the damned thing is half the battle. When you kayak in a river or lake, all you need to do is put the boat in the water, jump in, and paddle off. In the ocean, you must drag this rather heavy 12-ft. object past the breakers, which is a feat in itself. Once this is accomplished, you will normally find yourself in chest-deep water; you must then pull yourself onto the kayak, and flip around into the seat while holding onto your paddle. If you’ve managed to do this without getting overwhelmed by a wave… THEN you can paddle away.

But don’t paddle too far away. Once you’re beyond the point where the waves break, the ocean has a way of pulling you out to sea. You need to keep yourself in once place while easing back into the waves like a surfer does. At this point, your kayak can actually become like a surfboard, and you can cut into the waves and pivot off of your paddle. From there, the same common sense that applies to surfing applies to ocean kayaking. It’s not a good idea to get your kayak at a right angle to a wave — it can tend to push the nose of the boat down and pitch you forward into the shallows. Being clobbered by a capsized kayak or being driven into the sand by the unpredictable force of Mother Nature are not things you want to toy around with. Needless to say, it pays to be safe, and for god’s sake, war a life vest. If you’re at ease in the water (i.e. a good swimmer) and are somewhat cautious, this extreme sport is relatively safe. For the more adventurous, the best place to go is where the surfers are — around Indian River Inlet in Delaware.

GONADS FACTOR: Two gonads

SKI JUMPING

Maybe I’m nuts or just plain stupid, but when my friend Jim Cara asked me to go water ski jumping last month, I asked, “When?” I didn’t tell him that I hadn’t been water skiing in about seven years, never mind the fact that I had never dreamed of being pulled by a ski boat going about 30 m.p.h. over a five-foot ramp. It didn’t even daunt me when he told me the first time he went, he broke his ribs. At least it didn’t bother me right away until I thought about what happened to him last summer.

For those of you who are musicians and who read this magazine on a regular basis, you know Jim as an employee of Mid Atlantic Music and our former “Loud & Proud” heavy metal columnist. What you may not know is that Jim is an avid water ski jumper who had a little mishap last year. He hit the side of the ski ramp going about 50 m.p.h. The force of the impact demolished his right hand and arm, but after months of healing and physical therapy, he’s back and doing it again.

Jim took me out in his ski boat at the Upper Chesapeake Ski Club in Maryland one afternoon last month. As I said, at first I was pretty fearless about going jumping, but Jim did his best to freak me out. As we got in his boat, and he prepared the ski equiopment, he made little comments like: “Only a few people have died doing this. One guy died because he didn’t wear a helmet, and another guy hit the ramp and had his ass and back shaved off like a cheese grater,” he laughed.

I was more than a little freaked out when I saw the equipment — a helmet (the kind you wear riding a motorcycle), a special wet suit that has pads and braces to deaden your impact, and special kevlar gloves. What the hell were we doing, skiing through a combat zone?! As Jim put on his special suit, I noticed an odd loop that jutted from his waist. “Is that to hold your drink?” I joked. He demonstrated its use by threading his arm through it. He said it enabled him to jump further because, as he grabbed the tow line by the handle, his center of gravity would be near his hips, thereby enabling him to be flung through the air more efficiently.

As we waited for Jim’s coach, Ed Nichols, to show up, he took me for a spin in his boat. I asked him how fast it would go, as we pulled from the ski club. He lifted the lid covering the boat’s engine to reveal a 350 cubic inch car engine. “The cool thing about this boat is you can bank it going 45 m.p.h. without flipping it over. Here, I’ll show you.”

He told me to grab onto something. I sort of held onto the windshield. “Grab harder!” he yelled as we sped up. I sort of grabbed harder. Just then, the entire boat flipped around, sending me flying into Jim. The steering wheel hit my back, leaving a bruise in its shape, and my right foot hit something that raised a marble-sized welt. I was bruised and shaken, but Jim just laughed. “I could throw you out of this boat right now! Hold on we’re gonna do it again!”

We did it a few more times, and I started to get spooked. Up until this point I still had no idea how challenging ski jumping was going to be. We pulled over to the ramp, that actually had a sprinkler system on it to keep it wet, and it looked pretty ominous. Jim showed me the spot where he had hit the ramp — a nice-sized chunk of plywood was missing where his hand had been.

When Ed Nichols and his son, Don, finally showed up, we wasted no time getting Jim, Don, and Ed in skis and on the ramp in quick succession. The trick to ski jumping, as Ed related, is for the skier to build up his speed by cutting from the side just before he hits the ramp. While the boat only reaches a speed of 30 m.p.h. or so, the skier can reach 50 m.p.h. just by cutting. The three expertly demonstrated this technique and sailed through the air for almost a hundred feet before landing on their skis and skiing away. At one point, Don soared so high, he jumped beyond the frame of my camera as I shot his picture from the boat.

When they were finished, all heads turned to me, and my heart hit my stomach. I got a crash course in ski jumping from Ed as I donned his jumpsuit and nervously put on Jim’s helmet. “The ramp is slicker than owl shit,” Ed said. “keep your skis straight or you’ll slide off the side of the ramp.”

They soaped up a pair of jumping skis so my feet would slide into the, and I hopped off the boat and itno the water. Nervous tension built as I waited for the tow line to go from slack to taut. “Go ahead,” I croaked, and I was wrenched to the top of the water. Though it had been seven years since I had touched any skis, it all came back to me like riding a bicycle. I crossed over the wake as Ed had instructed, and my speed built as the boat turned around to approach the ramp. I tried not to stare directly at or even think about the ramp as it got closer. Before I knew it, my skis hit, and they reacted like they were sliding on banana peels. My feet flew in the air, I was hurtled into space, and my first ski jump of all time found me landing gracefully on my ass.

I jumped two more times — my next was a face plant, but to the surprise of all in the boat, I managed to land on my skis on my last attempt. Never mind the fact that I wiped out when I hit; I was just happy I hadn’t been maimed.

GONADS FACTOR: 3.5 gonads

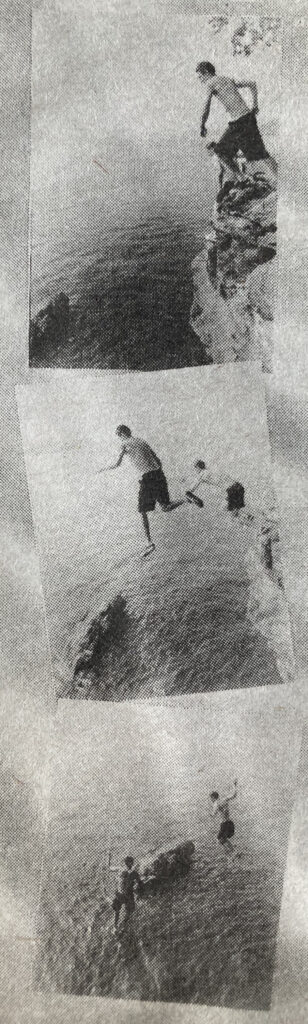

CLIFF JUMPING

The first time I went cliff jumping was about three years ago, shortly after I had gone bungee jumping. At this point in my life I was feeling pretty fearless. When my friend Shack told me about jumping from a set of 50-ft. cliffs near the Conowingo Dam off of Rt. 1 and Rt. 22 on the Maryland/Pennsylvania border, I told him I’d have no problem doing it. I had jumped from four times that height, attached to nothing more than a rubber band that threw me half as high back into the air. How could cliff jumping into water be worse than that?

But when we got to the cliffs the day we jumped, I adjusted my attitude. First of all, in order to get to the jumping spot, you must climb something resembling a goat path up the side of the bluff. In some areas, the path is as little as a foot wide, and the view affords you a pretty staggering vantage of the tumbling cliffs and water below.

Once on top, Shack shucked his shirt and spent little time thinking about it. I leaned over to look at the water 50 feet below. At first it didn’t look so bad, but when I saw Shack jump and how long it took him to hit the water, I developed new respect for the cliffs.

I stepped up to a spot crudely marked “44 ft.” in spray paint and prepared myself. When I looked down, I had the same feeling I had had weeks before when I was about to bungee jump. All the blood ran tto my feet and my chest got heavy. Instinctual fear took over. Nonetheless, I sprang about three feet away from the cliff and plummeted through space. I couldn’t believe how long it took to hit the water, and when I did, the force shut my jaw so hard, I had to feel my teeth with my fingers to make sure I hadn’t shattered them. That first jump I did in bare feet, but since the I have jumped in sneakers. The water hits you so hard, you find bruises in odd places on your body days later.

It was necessary for me to go cliff diving again last month in order to get pictures for this story. I went with Shack and our friend Mark, who had never gone before. We all jumped a few times, and as we made ready to leave, I packed my camera in its bag and proceeded down the path to the car. After leaping over a rock that blocks the path on the side of the cliff, my camera bag popped open, sending my camera and lens tumbling down the cliff into about 20 feet of water. It’s gone forever.

Of course, the only thing to do was buy a new camera and go back and do it later that weekend. It’s a good thing I did. Some kids who were there told me about the 80 ft. cliffs out at Peach Bottom.

It’s funny, whenever I tell my friends about the danger, pain, and even property loss associated with the cliffs, they’ll invariably ask, “Well, why the hell do you do it then?” My only reply is to quote the Red Hot Chili Peppers: “If you have to ask, you’ll never know.”

GONADS FACTOR: Five gonads