Interview: Exene Cervenka of X

The Return of X: Early Ancestors of Grunge

By GREGG KIRK

(July 1993, Big Shout Magazine)

Where were you in 1979? What were you doing when a group of four musicians erupted from the cramped bowels of the L.A. underground, poured a batch of vitriolic tunes on its complacent, pre-punk music scene, and forever changed the face of a form of music that would later be labelled “alternative?” What were you listening to just before you first heard of X?

In the days when stickle-haired guitarists beat their instruments as loud and as fast as they could and screamed about anarchy, and well before their longer-haired counterparts took the same angry energy and slowed it down, there were three misfit men and a woman pioneering the way. In a day and age where the word “grunge” connotes anything from a form of music to a style of clothing, X stands like a monument — an early ancestor of the school of loud and hard rock.

Pinch yourself. It’s happening again. After 13 years, four albums recorded with former Doors keyboardist Ray Manzarek and three more produced by various others, a turbulent divorce by songwriters and lead vocalists Exene Cervenka and John Doe, various personnel changes and a dubious four-year hiatus, X is back. And the music press is treating it like the Second Coming.

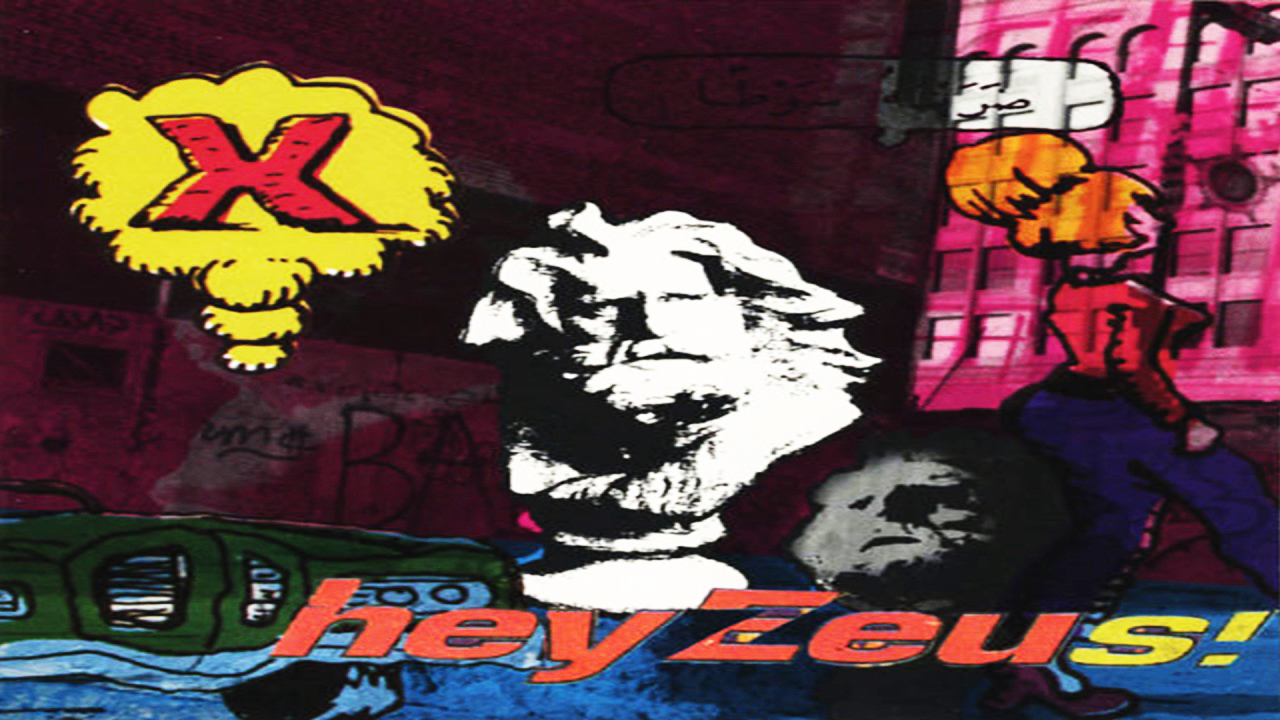

What tidings do these pre-grunge prophets have for us? With a new CD out (hey Zeus! on Big Life/Mercury Records), a high-rotation video on MTV, and a lengthy tour in progress, the X men and woman are an open book. Big Shout had a chance to talk to the Godmother of Grunge, Exene Cervenka, in a telephone interview shortly before the band made its way to the Chestnut Cabaret in Philly for an appearance on Tuesday, July 6.

Big Shout: Let’s start from the beginning. You guys formed in the late ’70s, and your first album came out in 1980. What was the L.A. scene like then, and who were the bands you hung out with?

Exene: There were a lot of bands playing but they weren’t all people we hung around with. They were people we went to see. Overall, it was pretty hardcore. The bands were really interesting and they were really varied in what they did. There were bands like the Plugz, and the Weirdos, and the Screamers, and those bands. But there wasn’t much happening then; it was right when things started happening, and we would open for the Dead Boys or a band like that.

BS: So it was pretty much a struggle because the scene hadn’t really been established yet…

EC: It wasn’t a struggle like it is now because it wasn’t a career like it is now. And there wasn’t a scene yet. It was like, you’d play a club and then you’d find out that you couldn’t get booked there again for a while because they didn’t like your show or something. We would play a show in a hall and then the people who owned the hall would say, “No, we’re not having shows here again like this. This was terrible, and there’s beer everywhere and vomit everywhere.” So they wouldn’t have another show there so you’d have to find another place. And somebody would call up and say, “Hey, I found this hall and we can put on a show, and I want it to be you guys, and the Dills, and the Avengers, and the Weirdos, and the Germs.” So we’d do it and charge $4 or something.

BS: How did things get rolling for the group? What was the chain reaction of things that happened to help move the band along?

EC: Well, I don’t think that things ever really have lines that are finely drawn. I think you play shows, and you work hard, and you write songs, and you record, and you go on the road. And that’s your life. And I don’t think…

BS: Well, maybe not that one “Big Break,” but weren’t there some opportunities that kind of opened up to you guys?

EC: There weren’t any opportunities every step of the way.

BS: How did you guys meet Ray Manzarek?

EC: He came to see us play.

BS: Okay, well that would be an opportunity.

EC: Well, it was an opportunity, but we were going to make a record anyway. I like Ray a lot, and I think that it was really neat that he was there. And I was thinking about him the other day — yesterday, as a matter of fact, because I was listening to a Doors song on the radio…

BS: Did he just stumble upon you guys?

EC: I think he read about the scene in the paper a little bit — early on — ’79, which was pretty early on. And he came to see bands and he saw us, and he thought we were a really good band. And when he started talking to us he realized that we were intelligent and articulate, and we read books, and saw movies, and we were neat people. And we were really young and doing something great. Because back then, there really wasn’t much in the way of culture — musically.

So we worked with him, and the first record we made with him — because he played on it and produced it — a lot of people really started to hate us at that point because we “sold out.” We made a record for $9,000, you know, (sarcastically) spent all that money and had this older person produce it. Now you see the Butthole Surfers with the guy from Led Zeppelin producing their record. Cool. Things have changed a lot. It used to be you weren’t allowed to associate with people past the age of 25. The punk thing became real rigid after a certain point — maybe around ’81 or ’82. It just got really stupid. There were these really goofy kids that came along that were real hardcore, and all of a sudden there were all these rules that all the original people had not thought up. Like spitting on performers, which was suddenly the thing to do.

BS: (Laughs) Did anybody spit on you guys?

EC: Are you kidding me?! Thanks to the media, YES! The media came out with this whole big thing about how in England, punk rockers spit. It seemed as thought a bunch of 14-year olds read it, and as soon as they could get into shows, they started spitting. And at first we thought it was rather humorous — these poor children didn’t know any better. But it just became an epidemic. You know, you’d walk out on stage and you’d just be covered with spit. And you’d try to explain to them from the stage or in interviews, “No, no we’re making music here. This is not England. That’s a myth. Blah, blah, blah.” But for years, it just kept up. And you’d see it all over the country until, like you know, even into the mid ’80s. And we just couldn’t believe it. You’d be on the road in 1986, and some kid would spit on you from the audience and you’d go, “God in heaven, where did you get this concept? Let go of it!”

BS: So what do you think of the scene today? Contrast it with what was going on when you guys were just starting out.

EC: I think it’s more similar right now to when we started out than it was like in the mid’80s. Now you’ve got bands like L7 and Eddie Vedder, and Johnette Napolitano, Green Apple Quick Step, Seven Year Bitch, and brand new bands playing these Rock for Choice concerts out here, and you just see these people, and they know who you are and you know who they are and they just come up to you and go, “Hey, I heard you guys made a record. When’s it comin’ out?” But you’ve never been introduced to the person — it’s just that kind of easy familiarity.

BS: You guys are being revered in your press as being at the vanguard of this whole thing, and while you certainly weren’t playing “grunge,” you definitely were an early ancestor of the style of music.

EC: Well, some of our songs were, though. Like “Nausea” and songs like that. We had a different style of music, but it was a style that we wanted to play. It’s weird, like when we would do a song like “Nausea” or “Blue Spark” or “White Girl,” a lot of times we’d get a lot of shit from the audience because they were slow.

BS: Do you feel like you’re enjoying a second coming now — with the new release and all the hype behind it?

EC: It’s much more of that than I thought it was going to be. I really thought that once we started playing shows again that it really wasn’t going to be a very big deal because it was before this huge success thing happening to all these alternative bands. Stone Temple Pilots, Pearl Jam, and Nirvana were all out there playing, but we didn’t realize that that scene was going to get so big. But there were a lot of bands happening that I really liked and that was inspiring to me — bands like L7 and Perry Farrell. And I thought, “That’s great. Here’s Perry Farrell selling 500,000 records. There’s a chance then that we can actually make a record.” But it seems like it’s a big deal to people that we’re back. It’s a big deal to our friends, I know that. They’re all really happy.