Interview: Live Aid’s Bob Geldof

By GREGG KIRK

May 1993, Big Shout Magazine

You’ve probably heard the story: Irish band the Boomtown Rats meet with considerable success in Europe during the early ’80s, shortly after the initial punk invasion of the late ’70s. Their popularity in America is hampered by the fact that their single, “I Don’t Like Mondays” (about an elementary student’s shooting spree), is pulled from sale and banned in the U.S. and by the mid ’80s their star has fallen in Europe as well.

In 1983, frontman Bob Geldof begins organizing a group of superstar musicians to perform on a single, whose proceeds are to be funneled to drought victims in Ethiopia. The project, called ‘Band Aid,’ suddenly swells into a larger project called Live Aid, and well… you know the rest.

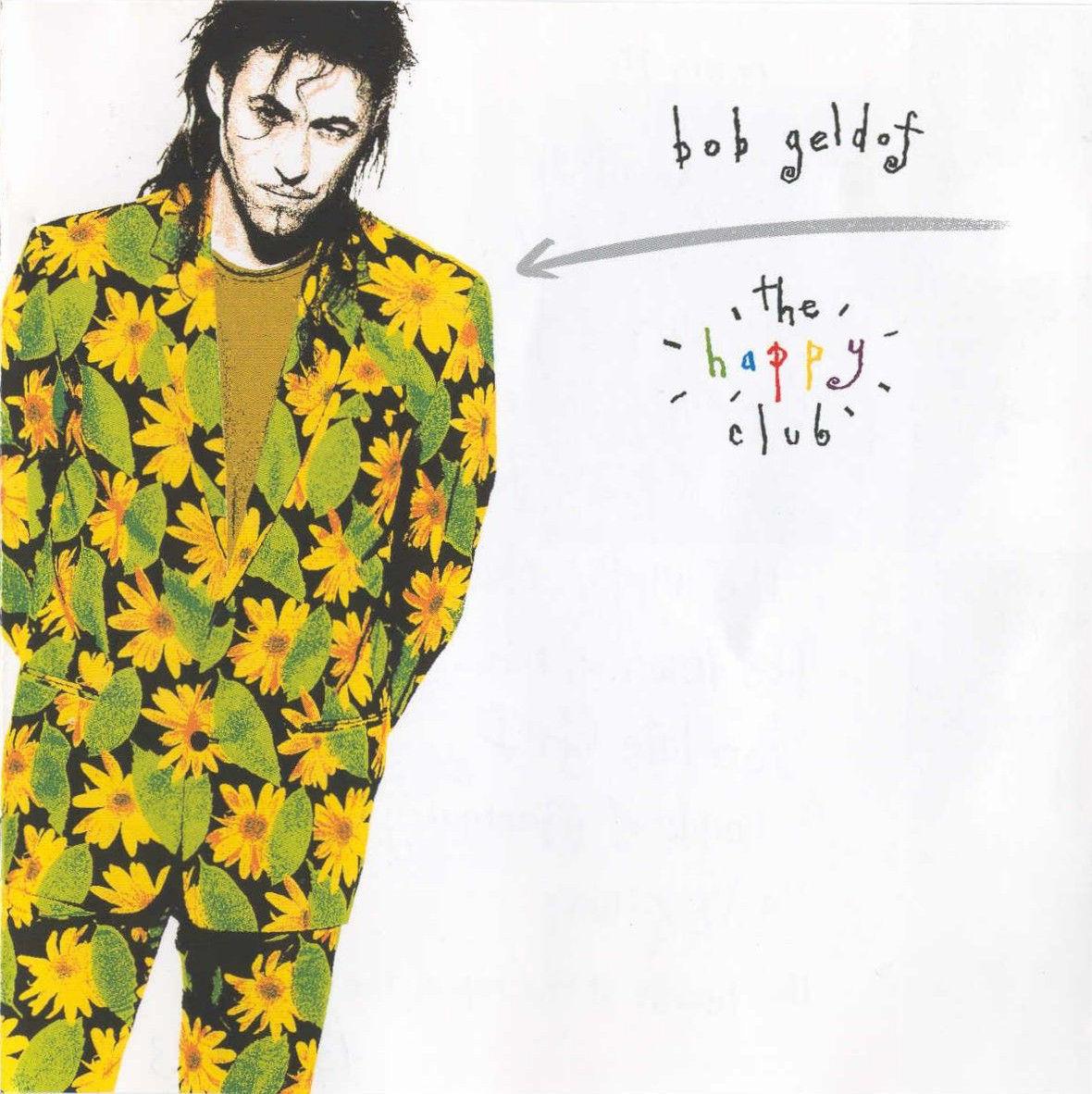

Or do you? Did life end for Bob Geldof after Live Aid? Did “St. Bob” (a title at which he openly bristles) take up residence beyond rock’s pearly gates? What follows is a telephone interview with Geldof shortly before his appearance at the TLA in Philadelphia on April 27 in support of his new release The Happy Club.

Big Shout: Give me a time frame here. The Boomtwon Rats fizzled out, and then you did the Live Aid thing, and then…

Bob Geldof: Actually the Rats thing came to an end after Live Aid. In reality, it had come to an end by then, but we did Live Aid and we did a thing in Ireland, and that was it. And then in ’86 I was still fairly fully occupied with the Live Aid thing, which had been three years happening then. I needed to get back to doing my job, which was music. And so I did some backing vocals for Darryl Hall, which was the first time I’d been in the studio for a couple years, and it felt so natural that I couldn’t wait to get back in. So Dave (Eurythmics) Stewart eased me along and aloft; I went to France with him and sort of hung out while he was working in the studio and then wrote a few songs and gradually got back into it.

And then I made Deep in the Heart of Nowhere, which more or less expressed exactly how I felt. I mean, if you’d been three years doing this stuff and seen what I’d had to see, which no one should see.. you know, it makes you feel pretty weird.

BS: I know you were frustrated for a while. I’d read different articles during the time after Live Aid that said you were uncomfortable with the “St. Bob” label you’d been slapped with and you wanted nothing more than to wash your hands of the politics and get back to music.

Geldof: That is true. Generally, it’s been an impediment, you know. Even now, you’ve got some knowledge of what I’ve done in the past. But generally you go along and someone will say, “Here’s that Live Aid guy. Okay, we’ll give it a listen.” So you’re burdened with your past, and then they might give you a charity fuck at 3:30 in the morning because “Hey, what a guy — he saved the whole entire world with his dick,” you know. Well, fuck off. Did you like the record? Okay, then play it. If you don’t like it, don’t play it. That’s cool. It’s equally cool with me, but don’t come as I am, burdened with baggage…

BS: So you’re still feeling it today…

Geldof: It’s not that I’m feeling it. It’s a fact of life.

BS: It’s still happening then.

Geldof: It’s not that I mind talking about it. Obviously, a lot of people took part by watching or becoming involved or by what they remembered, and that’s fantastic. That doesn’t bother me. It’s when it impedes what you do, you know. But I would imagine that hundreds of thousands of college kids have never heard of me, and I find that a great luxury to not have any history whatever.

BS: Speaking for people in America, I know you’ve achieved a certain level of success with your solo projects in Europe, but we’ve been kind of insulated from it here. I think a lot of people in the U.S. who are familiar with you are asking, “Is he still doing music?”

Geldof: Well, I don’t think they actually give a fuck. Maybe during an interview someone may say, “Is Geldof doing music?” And I think that’s a valid response if you haven’t heard anything about me at all. But Americans never really got the plot with regard to me. I mean, the Rats were known, but you probably didn’t know, for example, that “I Don’t Like Mondays” was never a hit because it was a banned.

BS: But I remember hearing it on the radio…

Geldof: Yeah, you heard it, but it wasn’t on sale. Our record company withdrew it.

BS: But sometimes that makes things more popular.

Geldof: Yeah, it only makes it popular if it’s banned, but if you can’t buy it… You know, like Ice-T and that, and something Two Man Crew, or whatever the fuck they’re called…

BS: Two Live Crew.

Geldof: There was all of this fury about them being banned, and then people rushed out by the millions and bought the record. But mine was actually withdrawn from sale.

Yeah, but generally in Europe they know about the Rats, they know about the Live Aid, but what they’re interested in is whatever the record is at the time. But again, it’s understandable — I haven’t played in America since 19 what… 81 or something? For me, going to Philadelphia is sort of intimidating because, I don’t know, who’s going to show up?

BS: There’s a certain syndrome that happens here in America, and especially in Philadelphia. When an artist is on an underground level, they’re highly respected, but when they start to make it big and move out of the city or country, they’re suddenly reviled. Is that the same type of situation in Ireland?

Geldof: Yes, very much. In Australia, they call it the “Tall Poppy Syndrome.” You have to be cut back down to the level of all the other poppies, you know?

BS: Did you personally, or did the Boomtown Rats, experience that kind of thing?

Geldof: Oh, absolutely… completely. That’s very much what it’s like in Ireland. It’s a very parochial, small country. It’s not so now because with the success of first the Rats, and then U2 and then Sinéad O’Connor and all that it’s sort of seen as a normal thing. But when we were starting off, like, for me to articulate ambition was to invite absolute derision. But that is a big problem. I’m surprised you asked that. It’s one of the things that drove me mad. It’s one of the things that made me leave.

BS: Wasn’t the band really kind of on the fringes of the whole punk scene during the time?

Geldof: Well, we weren’t allowed to be in because we were clearly saying that we wanted to write pop music — not stupid. You know, it would always have content. What does all of this posturing have to do with anything? The major problem with the world was not the fact that people were wearing flared trousers, as much as they would have liked to have thought it was.

BS: What was the inspiration for The Happy Club?

Geldof: I do an album every two years, so it’s really whatever is seen, or heard, or felt, and it’s not conscious. Write, record, promote, and tour an album — it takes a year and a half, and you’re sick of the fucking thing. And then you go away and do something else with your time. But in the meantime, all the stimuli you’ve experienced filters down to the brain pan and after about six months of doing stuff that’s not music, it begins to scratch and itch at your psyche. And eventually you feel full, like you’ve just had a meal. And that’s the time to move and get all the stuff out of you quickly. And that’s usually what it feels like.

BS: Are you apprehensive about coming to America to tour?

Geldof: That’s a good question. Honestly, yeah… probably. Put yourself in the place of going into a town where people haven’t heard of you. So I’m thinking, “What are they going to make of it, and who’s going to come? And what the fuck is going on?” It’s going to be interesting, that’s for sure.