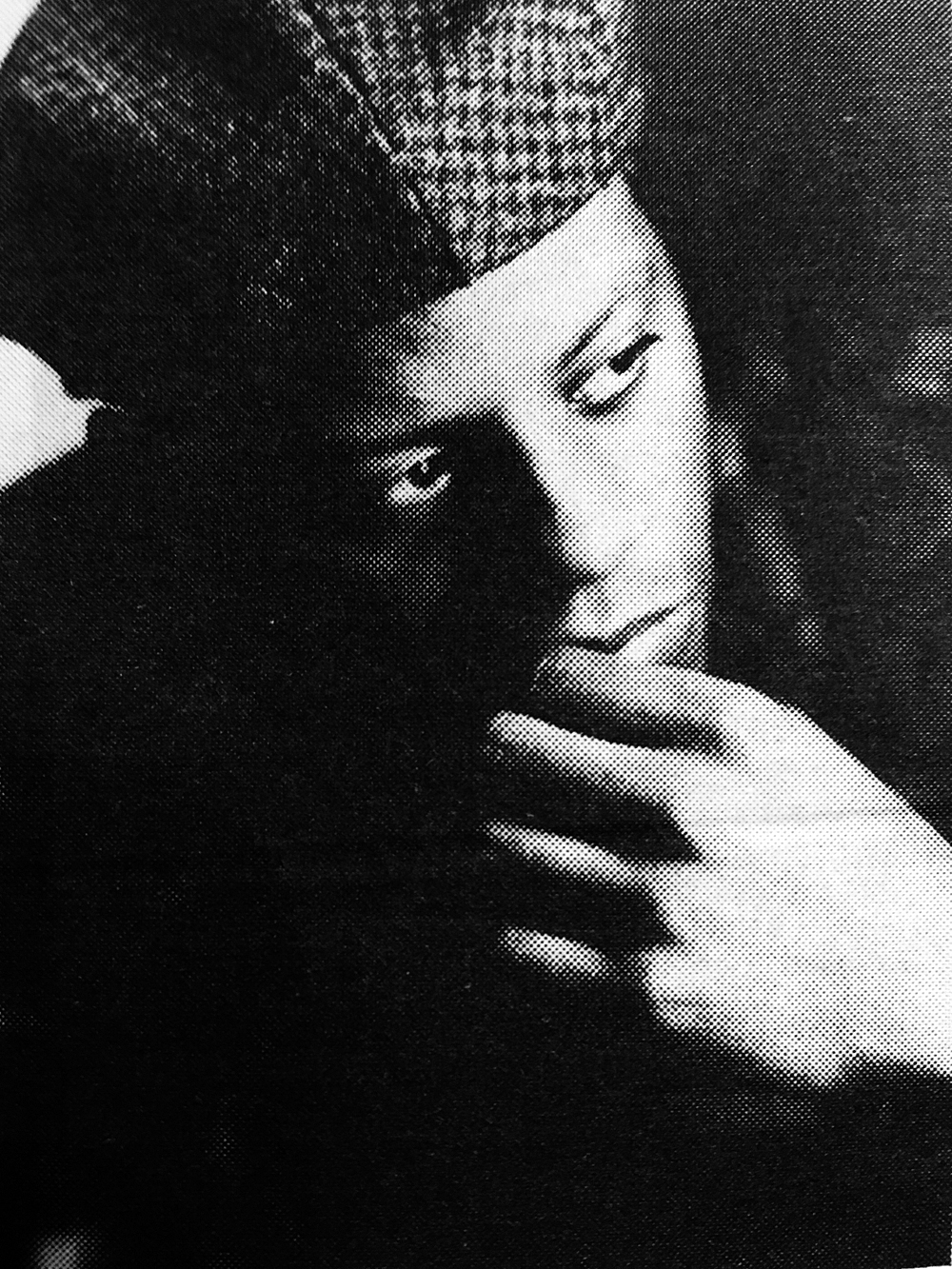

Interview: Schoolly D

Godfather of Gangsta Rap

By GREGG KIRK

February 1994, Big Shout Magazine

His name is Jesse Weaver, and he grew up in West Philly on 2nd & Parkside. In 1986, he teamed up with DJ Code Money to release a groundbreaking debut album that paved the way for the form of music that would later be called “hardcore” or “gangsta” rap. After a string of underground hits and subsequent snags with a handful of major labels, not much has been heard from the controversial rapper. Last summer, however, he was signed to Ruffhouse Records, who released his latest effort Welcome to America, and he now has plans for a national tour beginning sometime this month. It’s been a long road for someone who has somehow evaded the fame heaped upon every gangsta rapper to come down the pike. But with this new release, Weaver is determined to break the silence.

You know him as Schoolly D.

Big Shout: When did you start rapping?

Schoolly D: When everybody else started — in ’79. I started takin’ it seriously in ’83. I moved away from Philly for awhile; when I came back, everybody was doin’ it more seriously. I got into a group that was already established called the 5-2 Crew. I was the last one to get into the group and the one that went out there and started the record company. At that time, I knew it was going to be something different. People treated it as a game, but I knew it was like… crack. It was the new dope on the block, and I knew it was gonna surface. There was something I was looking for in my life and that was it. That was my shit.

BS: So you broke off from those guys and started your own thing?

SD: I didn’t really break off; they didn’t take it as seriously as I did. They was all into other things. Like I look at ’em now — some of ’em are selling dope, some of ’em are on dope, some of ’em are in the army, some of ’em are in jail, some of ’em are dead, you what I’m sayin’? I was the one who took it seriously.

BS: How did you go about starting your own label?

SD: It was easy back then because there wasn’t a lot of people doin’ it, and it was still fresh and new. The major labels didn’t want to have anything to do with rap so basically all you had to do was find yourself a studio, record, find yourself a pressin’ plant, press that shit up, and start distributin’ it around town, get the word out that you got somethin’ out to DJs and jocks who did stuff on the weekend at the radio stations. You got to the clubs and the stores and from the ‘hood, shit just carried out from Jersey to New York.

BS: How many records did you sell?

SD: The first album went gold (500,000 copies). Then I hooked up with a pressin’ plant and they had done stuff with Tommy Boy Records, so they knew where to send it. We struck a deal… I gave him an extra 50-cents for each record, and he took care of all my shipping. I just hired a staff, and we went to work promotin’.

BS: How long did it take to sell that many records?

SD: About a year. You know, but I didn’t actually get the gold money though because the whole thing was mob related…

BS: Mob related?

SD: Pressin’ plants then… it was their own personal gain. You know, I wouldn’t say mob, but gang related. It was more like, I’d go places and I’d find my record on other labels. You know how it is, it’s just like America only a certain amount of people gonna make the money. The music business is the same way.

BS: How did that work out?

SD: How did it work out? You got pressin’ plants involved, and all the pressin’ plants know each other, all the distributors know each other, you have so many independent companies out there. The only way I found out was I happened to be in Miami, and I was doin’ a lot of stuff with Luke Skywalker back then. He seen my stuff on another label, and he took me to the store and showed me. And the guy was like, “Yeah man, we move a couple thousand of those on this label every fuckin’ week!” Those were the days, man. You had to be hardcore to survive back then. It wasn’t nothin’ but gangstas runnin’ the music business if you go back to ’84 and ’85.

BS: I guess in that case it actually would have been better to get on some kind of small label because at least they could have looked out for you and gotten your money...

SD: No, that woulda been even worse. I had a fuckin’ six-figure bank account, cars, houses, dope, women. I was gettin’ money; I just wasn’t gettin’ the millions that I was supposed to have got. To cool the whole thing out it was almost like a pay off with money and my life. It was more like the pressin’ plant said, “Look, keep the shit quiet” — because they was already into some federal trouble anyway — “We give you X amount of money and your life, and you can fuckin’ walk.”

BS: Crazy.

SD: When I listen to hardcore music now, and these kids talkin’ ’bout they live a hard life and shit is hard, I’m like, “Yeah, okay.” I was there in the beginning. I knew what that shit is like. These recording artists coming out are like fuckin’ babies now. But you know what? That’s cool because this is why we did it then… so then the next wave of rappers wouldn’t have to go through the bullshit that we went through.

BS: You’re being billed as one of the original hardcore rappers. Are you comfortable with that?

SD: No, I don’t have any trouble with that. That’s because I was there in the beginning when there was like three of us, you know what I’m sayin?” Not 300 or 30 motherfuckers. There was just three of us who wanted to do it and who believed in it. There was Boogie Down Productions, Just-Ice from New York, I came out of Philly, Ice-T came out of L.A., and Luke was doing a thing called “ghetto style.” Well, there was five of us then, and it was all from different parts of the country and they all had different styles. Each and every one of us brought our own style, our own look, our own feel, and our own way of lookin’ at how we was experiencin’ life in our own neighborhood, you understand what I’m sayin’? I look at it now, I can’t tell who from where.

It’s good, then again it’s bad. It’s good because it shows a kind of unity that hip-hop has now — a big wave across the country. Then again, it’s bad because motherfuckers are following behind the next motherfucker.

BS: What’s your opinion of gangsta rap now?

SD: It’s entertainment now (laughs). You listen to one song, and somebody killed 30 motherfuckers… uh, that’s mass murder, and you know damn well mass murders in this country, nine times out of 10, get caught. If you still out of jail by the end of the album — you good! (Laughs) It’s more of an entertainment. I listen to a lot of young rappers, and I listen to what they talk about before they go into the studio and why the want to say that. They’re just blowin’ it all out of fuckin’ proportion. See with me, I stay fuckin’ real — I tell the real story and real accounts…

BS: But you’re talking about guns and killing people in your stuff, too…

SD: Yeah, but my shit is more realistic.

BS: Is that the kind of stuff you’ve been involved in on a personal basis?

SD: It touches everybody. It’s not about me, and Parkside Ave. anymore. It’s about America. It’s like the trailer when you go to the movies, “Coming soon to your motherfuckin’ neighborhood.” You know what I’m sayin’?

BS: What message do you have to young rappers?

SD: Start readin’. Motherfuckers don’t read no more, you know what I’m sayin’? If you want to know something about what’s going on in your neighborhood and all that shit, it’s cool to depend on fuckin’ rap, but they hopin’ that that’s all you depend on. When I say “they” I mean those motherfuckers that’s tryin’ to hold whoever you are back. Read the motherfuckin’ newspapers and read between the lines. Read the motherfuckin’ Newsweeks and find out what’s going on in other parts of the fuckin’ world. Start readin’ and start bein’ more aware in your surroundings. That’s what I got to say because that’s what my style of music is — to be more aware and to pay attention to what’s actually goin’ on. You can be entertainment also, but make sure you’re up to date on your current motherfuckin’ issues.