Local Breweries: A Rundown of Our Region’s Top Breweries

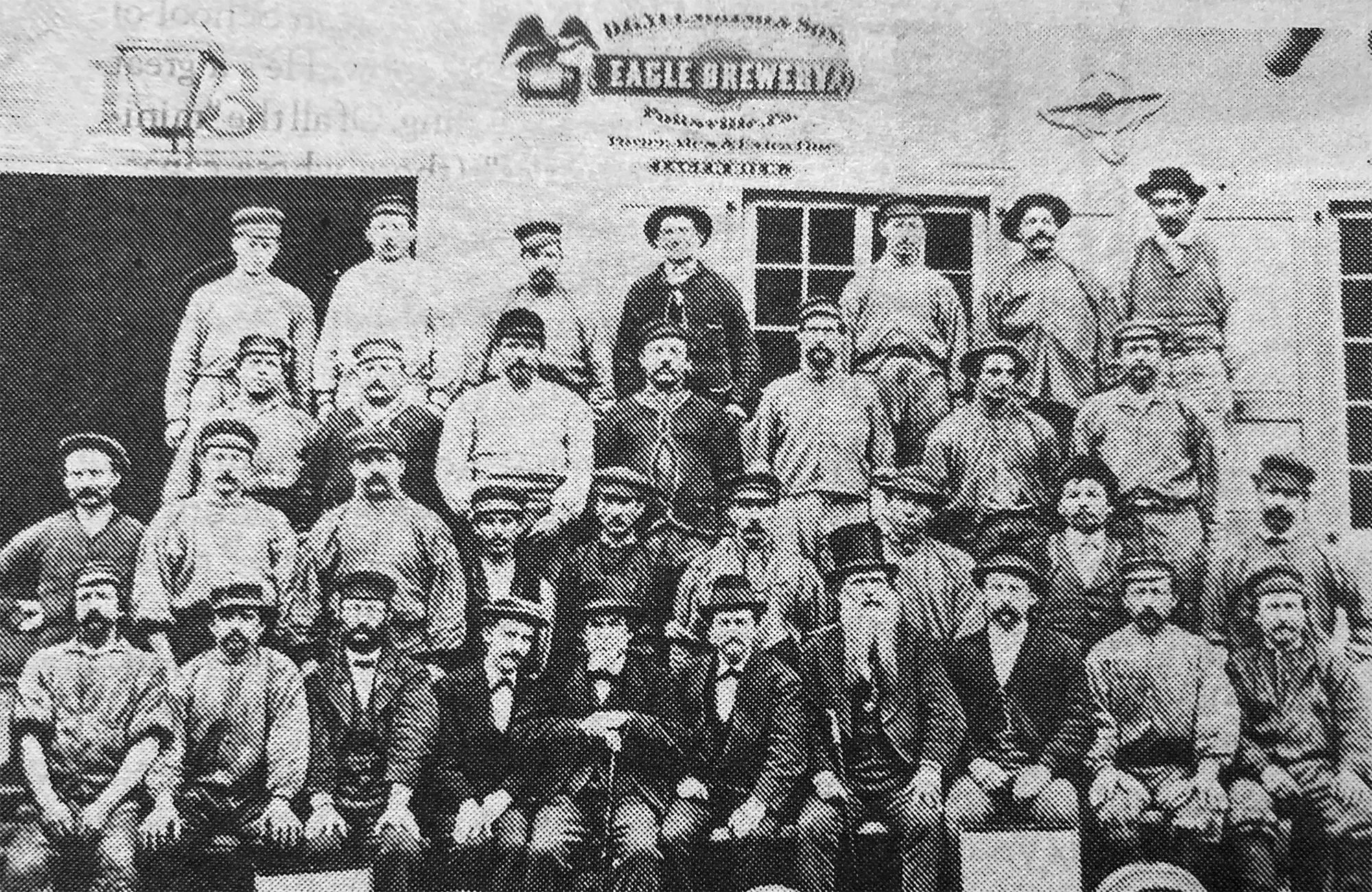

Founder David Yuengling (the stern-looking guy with the cane, front row center) and his crew circa the mid-1800s.

By GREG KITSOCK

Big Shout Magazine, August 1993

Every little village and hamlet used to have one — not just malt shops, drive-ins, or corner drug stores but breweries. There were more than 700 in the United States in 1834: more than 4,000 at the high-water point in 1873, delivering wooden casks of homemade suds by horse or goat carts. Most were driven out of business by Prohibition or the price whores, and multi-million-dollar ad campaigns of the large nationalists. As late as the 1970s, analysts were predicting within a decade or two, the remainder would be swallowed by Budweiser, Miller, Schlitz, and Pabst.

But something happened. Not only did the trend fold, but the industry was headed full-throttle in the opposite direction. Currently about 400 breweries exist in America, up by 800% since 1983. Many are recently-opened microbreweries and brew pubs. Some are regionals enjoying a new-found prosperity after years of hanging by their nails. Here are the thriving breweries and microbreweries in our region…

Latrobe Brewing Company

The maker of Rolling Rock, discovered that one way to co-exist with the big nationals is to become one yourself.

The brewery traces its history back to 1932, the cusp of the Repeal, when five brothers from the Tito family purchased a long-dormant plant in the western-Pennsylvania town of Latrobe, then famous for its Benedictine monastery. The Tito’s first customers were thirsty coal miners and railroad men within a 10-mile radius. Their flagship brand would eventually gain cult status as the “Coors of the East.” The name is appropriate: both breweries turn out a light, crisp, clean-tasting brew that was a novelty before every brewer and his aunt started making 96-calorie Miller Lite taste-alikes.

Both companies benefited from millions of dollars worth of free advertising thanks to Hollywood. Coors was touted in Smokey and the Bandit, while Rolling Rock was ubiquitous throughout The Deer Hunter (although I couldn’t help but notice that Robert DeNiro mis-enunciated it as Rolling ROCK, as though he were talking about an advancing boulder. The locals call it ROLLing Rock).

Latrobe Brewing has been extremely conservative: The same product in the same green glass for the last half century. The “33” on the bottle is as enigmatic as ever. Of all the fanciful explanations proffered for its presence, the most prosaic rings the most true. “33” was simply the word count for the ad copy to be printed on the package: The manufacturer of the prototype took it as part of the message.

In 1987, Latrobe Brewing was acquired by Labatt’s of Canada. The new owners began pitching Rock to a more upscale audience under the slogan “Imported from Pennsylvania.” Last year they sold more than 840,000 barrels in 48 states — a spit in the ocean compared to Anheuser-Busch’s 87 million barrels, but enough to make the roster of the 10 largest breweries in America.

By hitching up with Labatt’s, Latrobe Brewing has guaranteed its survival, but it lost something of its regional character. There are no tours, no hospitality rooms where thirst town folk or visitors can hoist a mug. Even routine calls for information are shunted to Labatt’s USA headquarters in Connecticut.

At the opposite end of the spectrum are the craft brewers called microbreweries. The definition of a micro is in constant flux as the most successful keep growing in barrelage. The Colorado-based Institute for Brewing Studies now accepts 15,000 barrels as the cut-off point. The first of these operations was the ephemeral New Albion Brewing Company, founded in 1976 in Sonoma, CA by ex-navy electrician Jack McAuliffe. That was jerry-rigged from dairy equipment and parts scrounged from junkyards. But as the number of microbreweries grew, consultants sprang up offering equipment, supplies, and advice to the small brewer.

Arrowhead Brewing Company & Wild Goose Brewing Company

Among the most respected craft brewers in the world is Peter Austin and Partners, LTD. of Hampshire, England. Austin’s protégé, a veritable Johnny Appleseed of brewing, is the 34-year-old Alan Pugsley. He has honed his skills in designing and installing small-scale brewing systems, developing new beer recipes, and helping new breweries achieve success with his guidance. You can visit Pugsley’s handiwork at the Arrowhead Brewing Company in Chambersburg, PA (50 miles southwest of Harrisburg) or at the Wild Goose Brewing Company in Cambridge on Maryland’s eastern shore. Don’t expect towering, red-brick Gothic buildings with stained-glass windows and statues to King Gambrinus. Arrowhead is nestled in a corner of an industrial park; Wild Goose occupies a former seafood processing plant.

Do expect first-rate beer. All of Pugsley’s 60-plus operations (they range from Dublin to Johannesburg) utilize a device called a “hot percolator.” The blossoms of the hop vine are steeped in hot water to extract every last bit of their aromatic resins. The wort, or unfermented beer, is pumped through this “hot tea” on the way to the chiller. This is what gives Arrowhead’s Red Feather Pale Ale, Wild Goose’s Amber, Samuel Middleton, and Thomas Ponte Light Ales a piquant, spicy bouquet you won’t get from Bud or Miller. The big brewers have been heading in the opposite direction. To avoid offending delicate palates, they’ve cut back at the threshold of detectability.

Pugsley’s operations are also distinguished by a special strain of yeast from the Redwood Brewery in England. Beer is a collaborative effort. Man cooks the grains to turn starches into sugars. The yeasts are one-celled but extremely clever organisms that chew up the sugar and spit out the alcohol and carbon dioxide. As byproducts of their metabolism, they also produce chemicals which can flavor the brew strongly. The what beer yeast used in southern Germany give the weizen beer a characteristic clove-like, almost medicinal taste. The wild yeasts that ferment Belgian lambic beers impart a mouth-puckering sourness. Pugsley’s Ringwood yeast is responsible for a dry, butty aftertaste that’s present to some degree in all of his products.

Last year, Wild Goose rolled out 4,000 barrels; Arrowhead 1,600. One industry joke holds that Anheuser Busch spills more suds in a day than than. Whether that statement is true or not, the combined output of the 400-odd microbreweries and brew pubs equals less than 1% of total U.S. beer production. But these self-styled, mom-and-pop operations account for 95% of the color, variety, and excitement in the industry.

D.G. Yuengling & Sons

D.G. Yuengling & Sons of Pottsville, PA isn’t aching to blanket the country. The closest the brewery has ever come to going national was in the late 19th century when it established short-lived branches in Richmond, VA and New York City. Today 90% of their sales are in Pennsylvania. Proprietor Dick Yuengling Jr., the fifth generation of his family to run the business, knows which side his bread is buttered. He recently pulled out several out-of-state markets, including Baltimore and the lucrative DC/Northern Virginia area to satisfy the clamor among local distributors for his products.

Pottsville, the seat of Schuylkill County, was frontier territory in 1790 when an itinerant New Englander named Necho Allen built a campfire on Broad Mountain and accidentally lit a vein of anthracite on fire. The discovery of hard coal brought the turnpike, canal, and railroad to the area and prosperity to Pottsville. Allen opened a tavern, serving a crude, butter liquor distilled from Hawthorne berries. Clearly, there was a need for more professionally made refreshments.

Enter David Yuengling, a German immigrant who had been chased out of Lancaster and Reading, PA by established brewers. He set up his first brewery on the current site of Pottsville’s city call. This operation burned down in 1831. Yuengling rebuilt the brewery on Mahantongo Street, burrowing deep inside the hillside to create aging cellars where the beer would remain naturally cold.

Yuengling’s heirs survived Prohibition by manufacturing new beer (which was sometimes spiked with ethanol when the Feds weren’t looking) and ice cream. In 1957, Yuengling became the nation’s oldest continuously operating brewery when the Boston Beer Company (founded in 1828) gave up the ghost. Prosperity didn’t really arrive until 1979, the brewery’s 150th birthday. The resulting spate of publicity finally convinced Pennsylvania what a good thing they had going.

Last year, Yuengling operated at capacity, rolling out 210,000 barrels. At a time when the national beer market is flat, Pottsville’s little brewery is adding up new storage tanks that will pump it’s output by nearly 25%.

Purists may fault Yuengling for using corn adjuncts in its beer products, even during the bleak ’60s and ’70s, when it seemed that all American beer was destined to become a clone of Bud or Schlitz. The flagship brand, Yuengling Premium, has a grimy, malt-accented flavor and a little more body than your typical pale American pilsner. The Lord Chesterfield Ale has a higher alcohol content and an almost floral aroma, thanks to a greater infusion of hops. A dark, mildly-roasted Yuengling Porter complete the roster. The latter style, which originated in 18th-century England, is supposed to have taken it’s name from the fact that it was popular among porters and heavy laborers. A more recent speculation — some 200 years ago, London pub keepers used to let some of the ale go a little stale to appease their customer’s tastes. When the keg has soured enough, they scrawled “potare” — Latin for “ready to drink” — on the cask. Either way, Yuengling brewed about 25,000 barrels of porter last year — more than any other brewery in America.

In 1991, the brewery opened up an extensive gift shop and museum to enhance it’s twice-daily tours. It’s worth planning an itinerary around. But there’s no rush — the proprietor has four daughters who should oversee the brewery into its third century of operation.

Editor’s note: Read a 1995 interview with Dick Yuengling Jr., to find out how the brewery and the proprietor’s plans changed in two years. Click here >>>

The Lion Brewery

About 50 miles north of Pottsville, in the Poconos, sits a regional brewery that didn’t make it. The Stegmaier sprawls along three blocks of Wilkes-Barre Avenue in the city of the same name, across the street from Joe Palooka’s Diner. The red-brick brewhouse looks like a beaten-up old prize fighter — shards of glass hand from the windows and ivy climbs the walls. A five-minute drive away, the Lion Brewery Inc., a much smaller, less ornate workaday brewery is operating at full steam. In 1974, the Lion bought out its larger neighbor and made the popular Stegmaier brand its own flagship label.

Bill Smulowitz, a graduate of Harvard and the Wharton School of Business, runs the show. He’s a great admirerer of Yuengling. Of all the mini-megabreweries (those whose capacity of between 100,000 and 500,000 barrels a year), only Yuengling is brewing the way a brewery did 25 years ago, making only beer and selling its own products.

Smulowitz’s route to success lies along another path. A recent tour group was told that only 15% of its output was beer. The lion’s share (no pun intended) consists of soda pop and malta, a non-alcoholic, mildly hopped cereal beverage popular among Hispanics, who regard it as a health tonic.

The Lion also serves as a brewery-for-hire for would-be beer barons who lack their own plant (like Neuweiler Brewing Company of Allentown, PA), as well as microbreweries who can’t keep up with the demand (Stoudt’s of Adamstown, PA).

Of the Lion’s own products, the most interesting are Stegmaier 1857 (an all-barley beer) and Stegmaier Porter. British beer writer Michael Jackson claims to detect a hint of licorice in the latter. Smulowitz, however, insists that his porter contains no syrups or additives, but derives its color and body solely from the roasted malt.

For those with taste for the exotic, Smulowitz has also dabbled in Red Baron (a cherry extract beer), Otto’s Oat Bran Beer, and Sting Ray gin-flavored clear malt liquor. None proved particularly profitable and all have been dropped. But it shows that there is no niche the Lion won’t try to exploit.

Smulowitz explains the business with a parable: “When the gazelle gets up each morning, he knows he has to run faster than the fastest lion to survive. When the lion gets up, he knows he has to run faster than the fastest gazelle if he is going to eat that day.” So, the gazelle, the lion, and Bill Smulowitz do a lot of running.